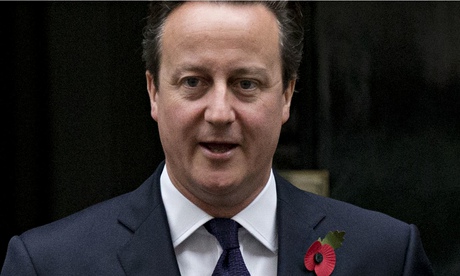

Cameron stands firm against drugs legalisation despite Lib Dem pressure

|

| David Cameron said: 'I’m a parent; I don’t want to send out a message that somehow taking these drugs is OK or safe. |

Prime minister says no to drugs policy review after report fails to find link between tough laws and levels of illegal substance use.

David Cameron on Thursday set his face against a change in UK drugs policy after the Liberal Democrat crime-prevention minister Norman Baker hailed a Home Office-commissioned report finding “no obvious” link between tough laws and levels of illegal drug use.Baker, minister responsible for drugs, said the report meant the genie was out of the bottle and was not going back in. He said: “I think the days of robotic, mindless rhetoric are over, because the facts and the evidence will no longer allow that.”

The deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, also urged the Tories to have the courage to break taboos, arguing that jail for possession of soft drugs should be scrapped and resources focused on “punishing the criminal networks, pushers and Mr Bigs”.

He added: “I think the Tories have a misplaced, backward-looking, outdated view that the public would not accept a smarter approach on how to deal with drugs. The argument I have made to them privately and publicly is, ‘pluck up the courage to face up to the evidence that what we are doing is not as effective as it should be, [that] there are lessons we can learn from other countries, and if you are anti-drugs you should be pro-reform’.”

However, Cameron said: “I don’t think anyone can read that report and say it definitely justifies this approach or that approach, but the evidence is what we’re doing is working.

“I don’t believe in decriminalising drugs that are illegal today. I’m a parent with three children; I don’t want to send out a message that somehow taking these drugs is OK or safe.”

The prime minister added: “Under this government, drug use is falling and I think that is because we have followed an evidence-based approach. We’ve been focusing on education, prevention and treatment, and that is the right approach to take.”

A No 10 statement rounded on Clegg: “The Lib Dem policy would see drug dealers getting off scot-free and send an incredibly dangerous message to young people about the risks of taking drugs.”

The 60-page report compared UK drug laws with those of other countries, including those that have decriminalised drug use, such as Portugal. It found that use of illegal substances was influenced by factors “more complex and nuanced than legislation and enforcement alone”. It said: “There is no apparent correlation between the ‘toughness’ of a country’s approach and the prevalence of … drug use.”

The research was commissioned after the coalition was unable to agree on setting up a royal commission on drugs. Baker accused Downing Street of suppressing the comparison report for months because it did not like the conclusions.

However, even Liberal Democrat MP Julian Huppert agreed the report was not totally conclusive. In a Commons debate he told MPs: “Although there is a serious gap where some of the conclusions ought to be … it is very clear. Sounding tough does not matter. The rhetoric does not make any difference.”

Labour’s home affairs spokeswoman, Diana Johnson, said the Lib Dems were “trying to solve a problem that doesn’t exist. Drug possession on its own is rarely the cause of a custodial sentence”.

She claimed the government had cut back spending on drug treatment saying: “In 2010, UK was a world leader in providing good-quality drug treatment and reducing drug harm. Over the last four years drug treatment is becoming harder to access and in some areas it is virtually non-existent.”

The Conservative chair of the health select committee, Dr Sarah Wollaston, said she wanted to see the evidence emerging from the US of the effect of decriminalisation, adding that cannabis use had harmed some young people. She pointed out that figures from Office for National Statistics showed the level of class A drug use among young people – 16 to 24-year-olds – had fallen by nearly a half, from 9.2% in 1996 to 4.8% in 2012-13.

Regarding legal highs, Baker said the government would look at the feasibility of a blanket ban on new compounds of psychoactive drugs that focused on dealers and the “head shops” that sell tobacco paraphernalia, rather than on users.

“The head shops could be left with nothing to sell but Rizla papers,” Baker said. “The approach of a general ban had a dramatic effect on their availability when it was introduced in Ireland, but we must ensure that it will work here.”

A ban would apply to head shops and websites. Currently suspected legal highs are banned on a temporary 12-month basis as each new substance arrives on the market.

The new generic ban would not be accompanied by a ban on the possession or use of the new psychoactive substances, which often mimic the effects of traditional drugs. This would remain legal.

Comments

Post a Comment